What did I find?

There’s a website named freeCodeCamp. It’s an online platform that teaches people of all education levels to code in various languages, including HTML, JavaScript, and Python. As one might guess from the website’s name and domain, it’s free to users and is run by a 501(c)(3). Since they are a public charity, they post data online for public consumption, which brings me to what I found: a table of responses from 4,751 new users in 2017, with diverse fields of educational and employment information as well as typical personal information like age. I also found the data for 2021, but I’ll be saving that for a longitudinal post a bit down the road.

Please note that this is not an advertisement for nor an endorsement of freeCodeCamp. It is just a dive into their publicly available data.

What’s in the box?

Our guiding question is: who is using freeCodeCamp? There are some interesting things to see on the way to an answer. I think we’ll find that freeCodeCamp does what it purports; provides a place where absolutely anyone can learn to code and launch a career in software development.

To perform this analysis, I used MySQL Workbench 8.0 to create tables and write and execute SQL queries. I made the data visualizations in Google Sheets using data from my SQL queries of the freeCodeCamp 2017 new coders survey database and the tables I created from it.

Age

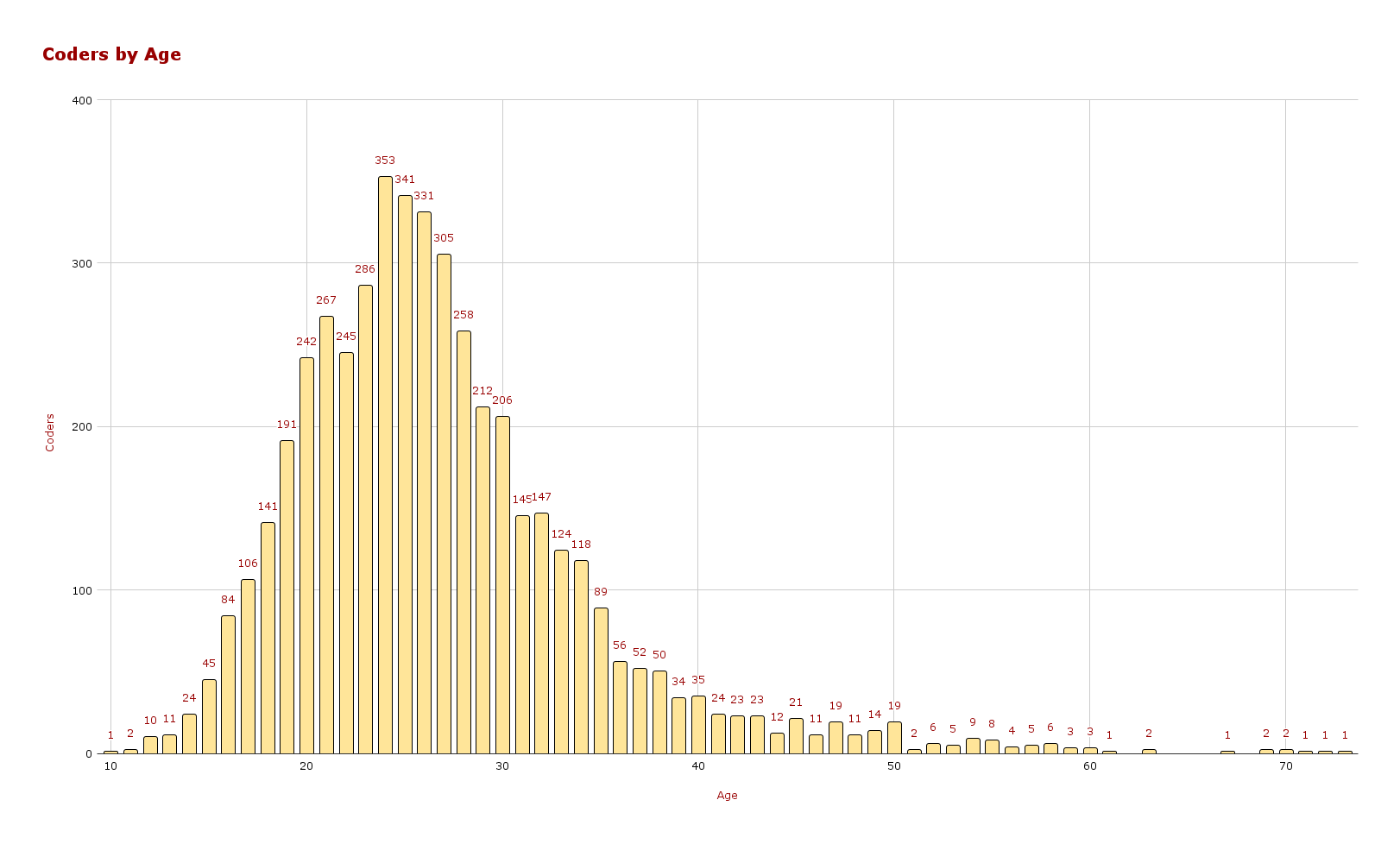

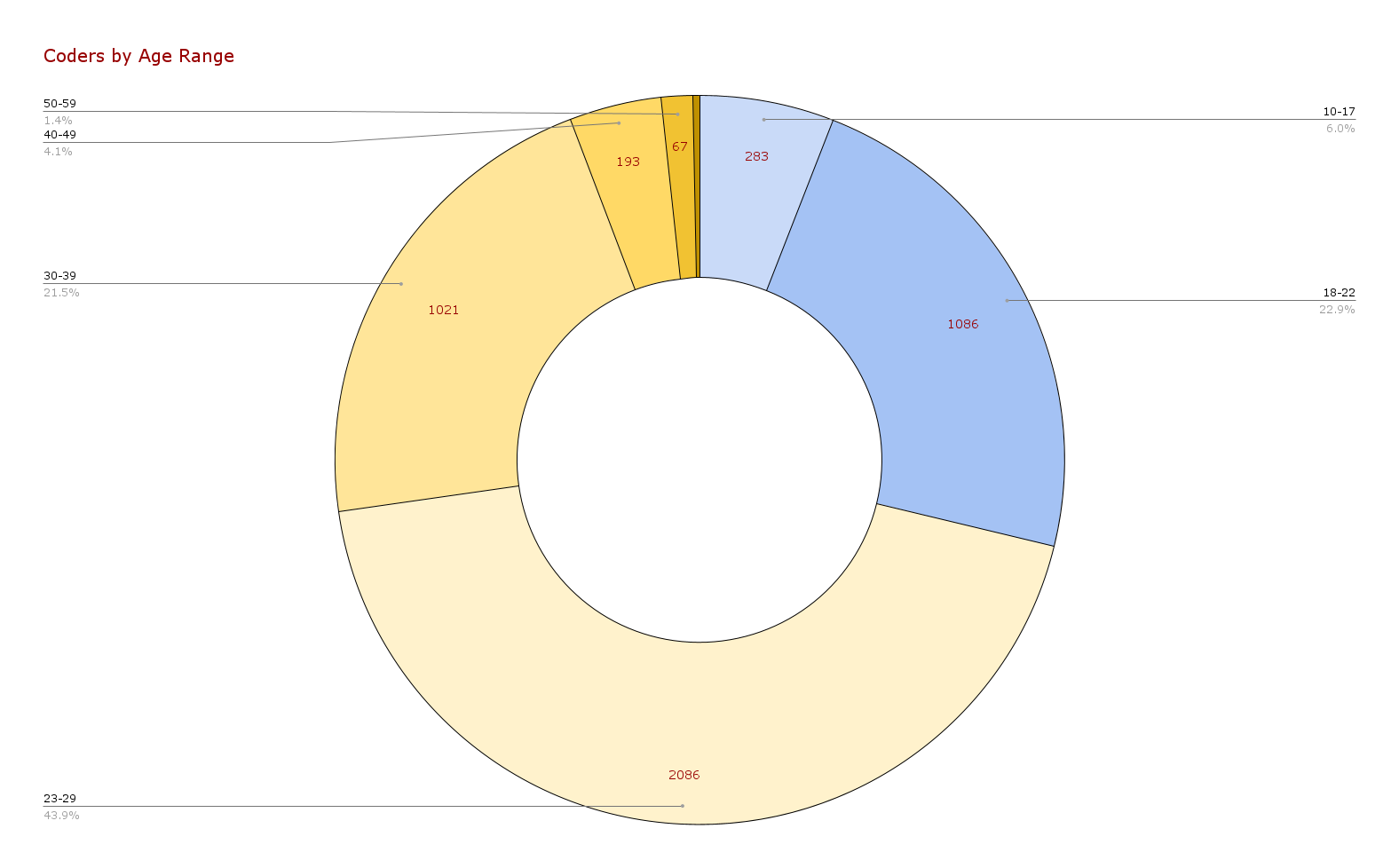

I guessed that I might find that freeCodeCamp was mostly used in secondary schools and higher education, but that doesn’t seem to be the case. In 2017, most of the platform’s new coders were in their 20s, and most of those were beyond typical college age. Before we dig further into that, let’s quickly say “kudos” to the 14 people who decided to learn to code in their 60s and 70s, and to a single, rather enterprising one-year-old whom I chose to leave out of my charts.

The data in this set shows that nearly 44% of coders who signed up for freeCodeCamp in 2017 were in their mid to late twenties — twice the percentage of either of the next two most populous groups (college-aged people and people in their 30s). Clearly my initial hypothesis was wrong, and the platform is being used much more by people who are working-age than by people who are likely pursuing formal education already. Of course this isn’t shocking, since that squares with the language on the website.

We can safely say that in 2017, more auto-didacts signed up for freeCodeCamp than students did, at a ratio of about 2.5:1.

Gender

The short story here is that the programming field still suffers from an enormous gender gap, and that in 2017, freeCodeCamp was not an exception to the rule. Of the 4,751 people who signed up that year, 3,752 identified as male (about 79%), 914 identified as female (about 19.2%), 26 identified as genderqueer, 18 as trans, 18 as agender, and 5 as genderfluid or non-binary (about 1.4% together).

While I’m pleased to see the effort that freeCodeCamp made to be inclusive on their form, I am somewhat aghast at the lack of parity. To put it lightly, this is not a representative sample of any large population, where gender is concerned. In fact, these numbers are closer to being what we’d expect to see in a monastery than in the general population — literally!

Education

More than half of freeCodeCamp’s new coders in 2017 (2,618 of 4,751) had a 4-year degree or higher level of education (Bachelor’s, Master’s, professional degree*, or Ph.D). This shouldn’t surprise us, given the age ranges we see above and freeCodeCamp’s mission. In fact, they state quite plainly in the FAQ section of the website that nobody should drop out of college to pursue freeCodeCamp.

*MBA, MD, JD, etc.

That being said, they also seem to believe that programming is a discipline that anyone can learn with the right tools and diligence (and I happen to agree with them). Though we have a self-selected group of new users without information about how many of them followed through, finished courses, and later got software development jobs, we can at least look at the 2017 new coder survey to see if that idea squares with who chooses to sign up.

I think the answer is a qualified yes, and we’ll look into that caveat in a moment. The largest group of new coders by education held a bachelor’s degree (1,881 coders or just under 40%). 17.3% had some college credit with no degree, which also isn’t surprising of a survey in which about 23% of respondents were aged 18 to 22.

That’s all well and good, but here’s the interesting — dare I say inspiring? — part. 174 new coders in 2017 had an associate’s degree. 111 had trade, technical, or vocational training. 563 had a high school diploma or GED as their highest level of education. 334 coders had some high school education with no degree. And 101 new coders had no secondary school education of any kind. Together, these groups total 1,283 people who chose to sign up for freeCodeCamp to learn a new skill and potentially get a job in software development. That’s 27%! It really looks like freeCodeCamp is accomplishing their mission, or at least attracting a lot of people who want to be a part of it. Whether those numbers meet freeCodeCamp’s own goals, I can’t say, but from the outside it looks quite good.

Now here’s that caveat: most new coders in 2017 already had jobs, and many of them were in the software development field.

Employment

freeCodeCamp is used by both employed and unemployed people, and we can divide up each group to find interesting information. In 2017, new users who did not describe themselves as employed made up 42.1% of respondents 18 or over (1,885 of 4,476). 1,082 of the 4,476 coders of working age described themselves as not working but looking for work, and 385 as not working and not looking for work. 2,519 respondents described themselves as employed for wages or as self-employed freelancers. That means at least 24.2% of working-age people who signed up for freeCodeCamp in 2017 were jobseekers and 56.3% were already employed. This information is self-reported and respondents could enter any text string into multiple fields at once, which is why those numbers don’t add up to 100%; some people were underemployed, some were students but working for their university, some had unpaid internships, etc.

We can learn more about these numbers by digging into the new coders’ employment fields, and this is where it gets really interesting. The first thing that’s really striking is the diversity of fields! Even though the number is off slightly from the true number of employed respondents because of shenanigans involving disparate entries between four different pieces of employment information, I found it very useful to create a new SQL table that consolidated only responses about current fields of employment. This allows us to see that, of the 2,582 new coders who provided information about their current employment field, only 1,324 of them selected “software development and IT.” That’s just 51.3%. Barely over half of employed people using a website that teaches programming languages were currently employed in the software development field! For those of you keeping track, that number is almost stunning when you look at the rest of the respondents. Only 29.6% of new coders 18 and older were employed in software or IT, or just 27.9% of respondents overall.

This means that there is a group of nearly equal size who are employed but looking to learn a new skill and perhaps completely change their field of employment. The largest single group who supplied their employment field were in education (173 new coders), followed by food and beverage (118) and arts, entertainment, sports, or media (114). There were also quite a few coders who described themselves as being in sales, office and administrative support, healthcare, finance, and many other fields.

Looking through the employment field responses was perhaps the most fun part of this analysis. I certainly want to give a shout out to the one new coder who was currently employed in the field of “Ice Hockey officiating,” the one new coder in “woodwind musical instruments manufactoring” [sic], and my new favorite person in the world, who in 2017 described their field as “Hula Hoopsmith/Just Started with Uber.” Congratulations, Hula Hoopsmith: you are the most interesting person.

So what’s the point?

freeCodeCamp seems to be attracting a lot of the people they want to attract. A large minority of new coders using the site in 2017 were in a field where they could be reasonably assured to get professional use from the skills they would learn on the platform. It appears that a majority of new users likely did not have that assurance, especially given that close to half were not employed at all. As far as I can tell, people really do sign up to freeCodeCamp in droves in the hope of launching a brand new career in software development. That said, we would certainly do well to remember the gender demographics; the lack of parity is frankly unconscionable. Not that that’s freeCodeCamp’s fault, as far as I’m aware. They even appear to have gone out of their way to make the site more by featuring women in two of the three testimonials on their front page, even though that’s roughly the inverse of their apparent user ratio.

The gender gap in programming notwithstanding, freeCodeCamp is for the people that they claim to be for. I think I’ll sign up, too.